Welcome to a new sneak peek on the YaST improvements you will enjoy in SLE-15-SP2 and openSUSE Leap 15.2… or much earlier if you, as most YaST developers, are a happy user of openSUSE Tumbleweed.

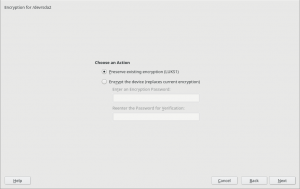

In our report of the 84th sprint we mentioned some changes regarding the encryption capabilities of the YaST Partitioner, like displaying the concrete encryption technology or the possibility to keep an existing encryption layer.

And the report of sprint 85 contained a promise about a separate blog post detailing the new possibilities we have been adding when it comes to create encrypted devices.

So here we go! But let’s start with a small disclaimer. Although some of the new options are available for all (open)SUSE users, it’s fair to say that this time the main beneficiaries are the users of s390 systems, which may enjoy up to four new ways of encrypting their devices.

Good Things don’t Need to Change

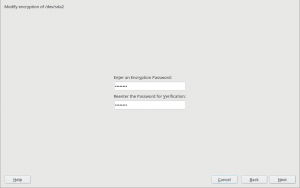

As you may know, so far the YaST Partitioner offered an “Encrypt Device” checkbox when creating or editing a block device. If such box is marked, the Partitioner asks for an encryption password and creates a LUKS virtual device on top of the device being encrypted.

LUKS (Linux Unified Key Setup) is the standard for Linux hard disk encryption. By providing a standard on-disk-format, it facilitates compatibility among distributions. LUKS stores all necessary setup information in the partition header, enabling to transport or migrate data seamlessly. So far, there are two format specifications for such header: LUKS1 and LUKS2. YaST uses LUKS1 because is established, solid and well-known, being fully compatible with the (open)SUSE installation process and perfectly supported by all the system tools and by most bootloaders, like Grub2.

You should not fix what is not broken. Thus, in most cases, the screen for encrypting a device has not changed at all and it still works exactly in the same way under the hood.

But using an alternative approach may be useful for some use cases, and we wanted to offer an option in the Partitioner for those who look for something else. So in some special cases that screen will include a new selector to choose the encryption method. Let’s analyze all those new methods.

Volatile Swap Encryption with a Random Key

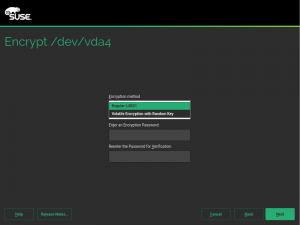

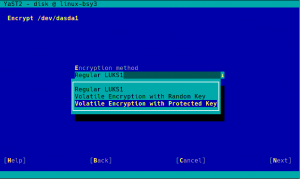

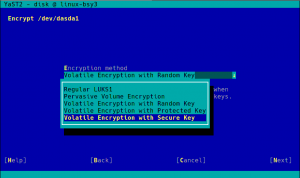

When a swap device has been marked to be encrypted, the user will be able to choose between “Regular LUKS1” and “Volatile Encryption with Random Key”. Both options will be there for swap devices on all hardware architectures. The first option simply uses the classical approach described above.

The second one allows to configure the system in a way in which the swap device is re-encrypted on every boot with a new randomly generated password.

Some advanced users may point that configuring such a random encryption for swap was already possible in versions of openSUSE prior to Leap 15.0. But the procedure to do so was obscure to say the least. The encryption with a random password was achieved by simply leaving blank the “Enter a Password” field in the encryption step. The exact implications were not explained anywhere in the interface and the help text didn’t mention all the risks.

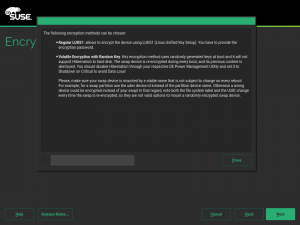

Now the same configuration can be achieved with a more explicit interface, relevant information is provided as you can see in the screenshot below and some extra internal controls are in place to try to limit the potential harm.

With this approach, the key used to encrypt the content of the swap is generated on every boot using /dev/urandom which is extremely secure. But you can always go a bit further…

Swap Encryption with Volatile Protected AES Keys

One of the nice things about having a mainframe computer (and believe us there are MANY nice things) is the extra security measures implemented at all levels. In the case of IBM Z or IBM LinuxONE that translates into the so-called pervasive encryption. Pervasive encryption is an infrastructure for end-to-end data protection. It includes data encryption with protected and secure keys.

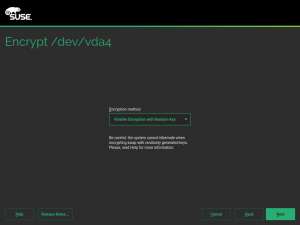

In s390 systems offering that technology, the swap can be encrypted on every boot using a volatile protected AES key, which offers an extra level of security compared to regular encryption using data from /dev/urandom. This document explains how to setup such system by hand. But now you can just use YaST and configure everything with a single click, as shown in the following screenshot.

The good thing about this method is that you can use it even if your s390 system does not have a CCA cryptographic coprocessor. Oh, wait… you may not know what a cryptographic coprocessor is. Don’t worry, just keep reading.

Pervasive Encryption for Data Volumes

Have you ever wondered how James Bond would protect his information from the most twisted and resourceful villains? We don’t know for sure (or, at least, we are supposed to not disclosure that information), but we would bet he has an s390 system with at least one Crypto Express cryptographic coprocessor configured in CCA mode (shortly referred as a CCA coprocessor).

Those dedicated pieces of hardware, when properly combined with CPU with CPACF support, make sure the information at-rest in any storage device can only be read in the very same system where that information was encrypted. They even have a physical mechanism to destroy all the keys when the hardware is removed from the machine, like the self-destruction mechanisms in the spy movies!

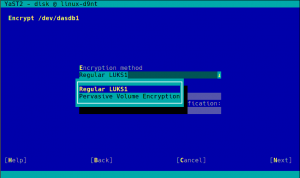

As documented here, the process to enjoy the full power of pervasive encryption for data volumes in Linux can be slightly complex… unless you have the YaST Partitioner at hand!

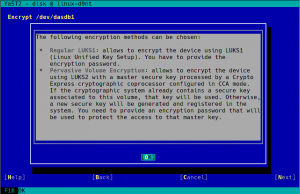

As you can see in the screenshot above, the process with YaST is as simple as choosing “Pervasive Volume Encryption” instead of the classic LUKS1 that YaST uses regularly for non-swap volumes. If YaST finds in the system a secure AES key already associated to the volume being encrypted, it will use that key and the resulting encryption device will have the DeviceMapper name specified for that key. If such secure keys don’t exist, YaST will automatically register a new one for each volume.

Pervasive encryption can be used on any volume of the system, even the root partition.

I want it all!

So far we have seen you can use protected AES keys for randomly encrypting swap and registered secure keys for protecting data volumes. But what if you want your swap to be randomly encrypted with a volatile secure AES key? After all, you have already invested time and money installing those great CCA coprocessors, let’s use them also for the random swap encryption!

If your hardware supports it, when encrypting the swap you will see a “Volatile Encryption with Secure Key” option, in addition to the other four possibilities commented above. As easy as it gets!

More Booting Checks in non-s390 Systems

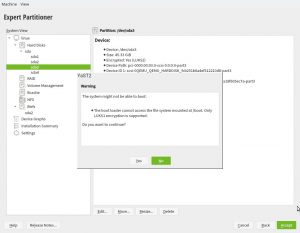

As described in the help for pervasive volume encryption showed above, that encryption method uses LUKS2 under the hood. So we took the opportunity to improve the Partitioner checks about encryption and booting. Now, in any architecture that is not s390 the following warning will be displayed if the expert partitioner is used to place the root directory in a LUKS2 device without a separate plain /boot.

As mentioned, that doesn’t apply to s390 mainframes. The usage of zipl makes possible to boot Linux in those systems as long as the kernel supports the encryption technology, independently of the Grub2 (lack of) capabilities.

What’s next?

We are still working to smooth off the rough edges of the new encryption methods offered by YaST and to add AutoYaST support for them. You may have noticed that most of the improvements currently implemented will only directly benefit s390 systems… even just a subset of those. But at the current stage, we already have built the foundation for a new era of encryption support in YaSTland.

We are thinking about adding more encryption methods that could be useful for all (open)SUSE users, with general support for LUKS2 being an obvious candidate. But that’s not something we will see in the short term because there are many details to iron up first in those technologies to make then fit nicely into the current installation process.

But hey, meanwhile you can play with all the other new toys!

Both comments and pings are currently closed.

>s390 systems offering that technology, the swap can be encrypted on every boot using a volatile protected AES key, which offers an extra level of security compared to regular encryption using data from /dev/urandom.

swap-with-random-key already implies a volatile key, at least if I am using the “swap” definition of crypttab(5), and I hope yast does too. So the “protected AES” key has no value over a random volume key, except that it is encrypted again(?) somewhere(?) with AES(?) for what benefit? The explanation is severly lacking, the more so the dropdown box.

At the very least, it should be “Encryption with volatile random key” in the text, because the encryption is not volatile (the data is basically still there after a reboot), but the keys are (gone after a reboot).

For more details about using a volatile protected key for swap encryption, you can check this document https://www.ibm.com/support/knowledgecenter/en/linuxonibm/com.ibm.linux.z.lxdc/lxdc_swapdisks.html

And about the label, your are right. “Encryption with Volatile Random Key” would be more correct. We will change it. Thanks for the feedback!